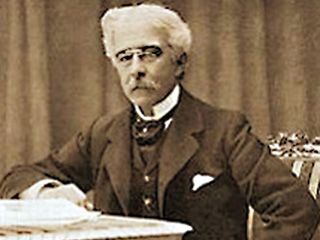

Antonio Fogazzaro

Piccolo mondo moderno [The Man of the World]

Piero has the moral weakness typical of Fogazzaro’s male characters, but he is destined to be called to his vocation. Jeanne is a temptress, troubled and sceptical. The reader is left feeling that perhaps she is sincere in her behaviour, seeking the elevation of the soul rather than mere perversion. They are at once attracted and repulsed by their love for each other. Here again, natural elements intervene and interact with the characters. For example, in the grounds of Villa Fogazzaro Roi Colbachini (“Villa Flores” in Piccolo mondo moderno) in Montegalda, when Don Giuseppe, Piero Maironi’s confessor, meets Piero’s mother-in-law, the “sorrowing and weary” Marchesa Scremin, the garden is protagonist, the ideal place for their silent communication:

A grouping of clear notes around the calm movement of a slow melody, neither gay nor sad, would alone have the power to express that intangible inward something that escapes the poet when he seeks to describe the slow progress of Don Giuseppe and the Marchesa among the grasses swaying in the wind beneath the flickering shadows of the silvery clouds, among the bushes the whispering of whose leaves was interrupted by the sad, persistent notes and soaring runs of nightingales. The couple exchanged hardly a word, and therefore only music could describe this silence so full of meaning, this not unconscious communing of their souls, a communing expressive of mutual pity; the Marchesa reflecting how the old priest, cherishing a gentle, poetic hope, had prepared these beautiful surroundings for his dear ones, now, alas, all descended to the grave; Don Giuseppe reflecting upon the kindness of this sorrowing, weary woman, who, to please him, was exhibiting such an interest in his garden; the hearts of both were soothed, meanwhile, by that most lasting of earth’s pleasures, a calm appreciation of the beautiful.

And then there are the flowers: in the moonlit garden of “Villa Diedo”, namely Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza, the restless roses sway seductively, intensely mirroring Piero’s quivering passion. They echo the young man, leading Jeanne towards temptation as she stands clothed in the same white as the terrace, a symbol of purity, igniting forbidden desires:

Jeanne was standing behind the balustrade, a small, white cape thrown over her shoulders. “This is good of you!” she said in answer to his respectful salutation. Hat in hand, Piero went up to the terrace with a smile upon his face that was too much like the smile of the woman who was advancing to meet him. It was indeed magnificent in the moonlight, this white marble terrace, jutting out from the first floor of the villa with its flight of broad steps leading down into the garden, its balustrade which the creeping roses had taken by storm and hidden beneath a tangled glory of dense foliage and great flesh-coloured eyes, long branches swaying in the vagrant breezes of the night. It was magnificent with its surrounding circle of beauty, sweeping from the dark and humble plains on the North to the radiant brightness in the sky above the lighted city. “Why not stay here?” Piero said in an undertone as if the innocent words might betray to some inquisitive ear his longing for an hour of delight in that solitary and enchanted spot among the restless roses, which rustled a voluptuous invitation.

And again the roses in “Villa Diedo” (Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza), murmuring voices alternating between torment and passion:

Only a thin, silver rim of the moon reddish globe was still shining when they once more ascended the dark terrace. In the restless air, the swaying of the roses, indistinctly heard, sounded like the voices of desire and pain. The sprays seen but indistinctly, waving from side to side, seemed like the arms of staggering blind men. As he leaned forward to turn the reclining-chair towards the west, where the moon was setting, Piero brushed Jeanne’s shoulder with his lips.

Then we come to Vena di Fonte Alta, which is, in fact, Tonezza del Cimone. The fog acts to isolate Jeanne from the earthly world, nudging her gently into a world of purity. It resonates with her heart-felt desire for a life together with Piero, but it also forebodes that their union will only be a spiritual one.

A veil had fallen on the emerald of the fields; the shadows of the trees had vanished in the diffused light of the sun that was concealed; the dense fog that had come smoking up from the valleys was invading all the upper hollows of Vena and the tops of the forests, deadening the sound of the scattered cow-bells in the pastures, enveloping and darkening the slopes of Picco Astore. It seemed to Jeanne that a damp white cloak was descending upon the soft fields, was enwrapping Piero and herself in its woolly folds, was cutting them off from the world of human anxieties, from the past and from the present, and filling them with a sweet sense that they were souls of another planet. She realized that an hour of supreme importance was approaching, that there hung in the balance not only her own fate and happiness – what did they matter, after all? – but the happiness also of the man she loved, the man who was being led astray by fatal dreams. Timidly she passed her hand through his arm, whispering: “Do you mind?” And although his “No” had a cold ring she pressed her lovely form to his side. “Dearest!” she murmured.

After this decisive moment, the inebriating fog again returns, but then lifts to reveal the soaring mountains centre stage, and these very mountains seem to confirm Jeanne’s foreboding that earthly love for Piero will be impossible:

And slowly, very slowly, the young man’s face did indeed approach hers, which was composing itself slowly, very slowly, and was lifting itself gravely towards the meeting. Then their two souls that had risen to their lips uttered a thing so wonderful that when their lips parted at last, their eyes could not bear each other’s gaze. It was not the first time Piero and Jeanne had met in that unspoken thought, but they had always met with hostility. Now it was no longer so. Now the woman knew that there was one repugnant way of binding her lover for ever; the man knew that there was one sweet way of riveting his chains for ever, and he saw that her resistance was shaken. Both, at once attracted and repulsed, trembled with emotion. Meanwhile an unpleasant wind had sprung up and was blowing the fog into their faces. Jeanne and Piero started towards Rio Freddo, she leading the way in silence, conscious of his eyes fixed upon her, and turning her head to smile at him when that gaze became so piercing she could not bear it. Little by little the fog lifted, and on the left there loomed, black and towering, the tragic Picco Astòre.

We conclude this series of images with the mountains: Vena di Fonte Alta is in fact Tonezza del Cimone, “five hours from the city, two hours of train and three by carriage; it lay one thousand metres above the level of the sea, and offered the attractions of pine-forests, beech-groves solitude and quiet”. Fogazzaro first describes it almost as an animal, but then softens and and we sense a loving familiarity with the place.

The spur that bears Vena di Fonte Alta stretches forward from the base of Picco Astore, its twin horns facing the great stone quarry of Villascura. Towering above the abyss that encircles them, the pine forests and beech groves of Vena wave against a background of sky, spotted here and there with pale emerald, where the fields press them asunder and overflow, and dotted with red and white where small houses are huddled together in groups. He who contemplates them from the top of the sloping and soaring Picco Astore, or of the lofty, cloud-capped mountains of Val di Rovese and of Val di Posina, may not realize their delicate and exquisite poetry. But the wayfarer who threads their winding depths asks himself if, when the world was young, this was not the scene of the short loves of sad spirits of the hills and of gay spirits of the air; if the earth, in obedience to their varying moods, did not transform itself around them again and again, now forming shady marriage-beds or leafy couches for reposeful contemplation, now surrounding them with scenes of melancholy or of mirth, of great thought or of merry jest; which changes ceasing when the lovers suddenly vanished, the earth retained for evermore the form it had last assumed. Every object bears the impress of a sentiment.

As his wife’s health worsens, Piero leaves Vena and the panorama rushes past. The landscape is described in all its aspects, it holds so many secrets, and Piero dwells on his thoughts, examining his conscience as the old horse trots rhythmically, arousing forebodings and dreary expectations.

Down, down into the darkness he went behind the slow-trotting, jaded horse, perched on the crazy cart beside a mute companion. Above him the woods, the pastures with their paths, the thickets, the fountains that knew so much of his secret, and Picco Astore itself were vanishing for ever. Down, down beneath the glistening stars, now following a bare slope, now passing black groups of narrow cabins. Above him the house where Jeanne, all unconscious, lay sleeping is vanishing for ever. Down, down behind the jaded, slow-trotting horse, through a grove of sleeping beeches, the vanguard of a few firs that are awake and watching, and along the curving brink of precipices. Down, down with the haunting horror of the betrayal he, in his selfishness, had been planning. Down, down from the cold winds of the heights into an atmosphere that grew ever more stifling, with the vision of his whole sad life.