Reading Fogazzaro’s novels and walking can help cultivate a sensitivity towards our surroundings, we will be able to admire the landscape as it tells its story, we will explore and rediscover its forms, we will learn not to remain indifferent, but rather, to stand in awe, and people will be drawn to an experience which is both invigorating and culturally enriching. As we succumb to the influences of literature and the landscape, our eye will be more perceptive to Beauty.

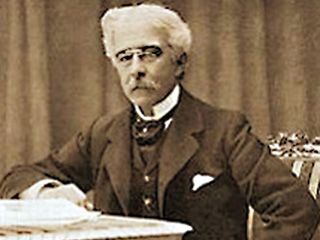

Antonio Fogazzaro was born in Vicenza in 1842 into a wealthy family who was actively involved in the struggle against the Austrian Empire. He was taught by the poet Don Giacomo Zanella, an eminent literary figure in Vicenza. In 1864, he graduated in Law at Turin and then lived in Milan where he practised as a lawyer. He married Margherita Valmarana in 1866 and three years later he moved back to Vicenza to dedicate himself to his literary career. He was a member of the Congregazione della Carità (a state-run charitable association) and of the Provincial Board of Education, and he held political positions as a local councillor and Italian senator. He was the chief Arbitrator for the Banca Popolare di Vicenza and was Chairman of the Società del Quartetto and the Accademia Olimpica.

Following his short poem Miranda and his collection of verse entitled Valsolda, his first novel, Malombra was published in 1881. However he found fame and success with his later novels, Daniele Cortis (1885), Il mistero del poeta (The Mystery of the Poet, 1888), Piccolo mondo antico (The Little World of the Past, 1896), Piccolo mondo moderno (The Man of the World, 1901). His last two novels, Il santo (The Saint, 1905), and Leila (1910), were banned by the church and put on the Index.

We can begin to build a portrait of Fogazzaro with two powerful pictures. The first is as “Cavaliere dello Spirito” (Knight of the Spirit), as he is depicted in letters to Matilde Serao, describing Fogazzaro as a writer who dealt with issues such as the crisis of the family, the need for reform in the Catholic Church, and the relation between faith, science, eros, and morality. The second is how Giovanni Papini described him, a deep-sea diver, plumbing the murky, monster-filled depths that is the human soul, given that Fogazzaro is most concerned to describe the complexities and ambiguities of the modern soul. To these pictures can be added that of the gentleman writer, a man accustomed to living in elegantly furnished, aristocratic villas, wealthy, unencumbered by the cares of a practical life, skilled in the art of observing things and souls, with a graceful hint of poetry.

My vision of the world is different from the one my fellow artists see, different from the real world. I do not see the great men that others see, but I see great women that nobody knows about. In all souls I see reflected the glow of an unknown light, a sovereign idea. I neither sell, nor break my spectacles, but rather I keep them, I have them gold-plated as a reminder of the warm and generous fire in my heart when it was deluded, but happily so, into thinking that I could use them to penetrate the universe, to glean from it, as my own idea of art told me, phantoms of eternal souls or living shadows of beings, as a reminder of some faithful, burning spirit.

And again Fogazzaro wrote about himself and his experience as a writer:

My books are drawn in part from other books, in part from the truth in things, and in part from the depths of my own soul; because my soul, too, is a sky filled with shadows and stars which rise and set and rise again without rest, and therein lies an abyss so deep that not even the inner eye can penetrate it.

Here, Fogazzaro provides us with the sources for his works: other authors’ books, the “truth” in his surroundings, his experience, and contemporary religious and political characters, but especially the “truth” in his exploration of feelings and our destiny as humans. Fogazzaro explores his own soul, fraught by the tensions between virtue and passion, but also driven by Christian evolutionary theory, by his own political commitment and by spiritual pantheism.

Other aspects of Fogazzaro’s personality can be gleaned from the comments of another writer from Vicenza: in an article written in 1942, Guido Piovene cleverly draws remarkable analogies between Fogazzaro’s character and the contours of his landscape:

He shied away from things which were too well-defined, from the harsh lines of residential areas; Vicenza and its surrounding landscape, so softly nuanced, so fleeting and elusive, made up of so many individual elements which nevertheless defied an overall definition, was perfectly suited to his temperament. The landscape is a collage where the languor of Venice or blessed skies across the plains, laden with the scent of the sea, perhaps even the East, lie within close range of the crested Dolomites and the vast valleys beneath them. All this pleased Fogazzaro, it suited his uncertain spirit, always aspiring to something higher, swaying between a host of often conflicting fantasies, and for each of them he would seek out the soothing embrace of both the meadows,and the woods, and the mountains. Yet he also enjoyed life in the villas, as nowhere else had the art of sojourning in villas reached such unparalleled levels of perfection. One of the most frequently occurring landscape images in his art is the joy that could be felt before a bare peak, sheer rock, soaring upwards like a cry renting the silence, yet bursting forth from the lush greenery, the sensual and blossoming life in the woods and meadows. One might say that he disdained the conquered heights of the mountains preferring to view them from below, when they still appeared to him as something to aspire to, a fairytale, a fantastical place, in a sense the ideal of an unfulfilled spiritual life.

In Fogazzaro’s novels the landscape is not a static element but behaves as though it were alive, underlining the shifting feelings of the characters, it makes its entrance like an “actor” and reacts with “prompts”.

We can add further colour to the portrait of the novelist with fragments relating to Fogazzaro the “geographer” and “botanist”. These aspects may well draw readers to his novels as Fogazzaro was not only a careful observer of the human soul, but a lover of Nature.

From the great slopes of our mountains to our poetic sea shores, nature has lavished on us so many scenes of incomparable beauty that we may imagine any kind of scene set there, from the most grim to the most hilarious! […] only a very few observe our natural surroundings.

Fogazzaro was a “geographer” and “botanist” because he expressed that love for the landscape, for plants and flowers, which is bound to everyday experience and charged with memories. The places he described were not merely a backdrop but places he knew and loved, a collection of clearly identifiable places in Montegalda, Vicenza and Val d’Astico, and like all good geographers he measured space in a very simple way – by walking. It is a recurring theme in his novels and the moment when the characters reveal their deepest emotions, be it curiosity, fear, enthusiasm or even passion.

Fogazzaro the geographer discovers that “little” world of serenity embedded in his native land, not by means of a quiet life, but through familiar gestures, through sacrifice and pain. However, his little world is riven by the anxiety of the soul and the precarious nature of human relationships.

Fogazzaro’s originality lies in his interpretation: in his novels the landscape is not cold and impersonal but a living being who is transformed and alive, it interacts with the anguished events surrounding the characters, it is both mirror and interlocutor, it conveys messages and approval, it is the confidante of the hidden truths in the characters’ souls. Lovingly, Fogazzaro re-evokes the places of his trembling and suffering soul, his refined gaze lingers there tenderly, and the reader is invited to inhabit this space and partake in his “little” world. However, while the city is a place of mystery and solitude in this world, the ideal place to live is the countryside where one can aspire to live peacefully, sheltered from all care and worry in an enchanted place (suited, as Piovene said, to Fogazzaro’s “uncertain” soul “aspirating to something higher”).

There is still another element to help discover Fogazzaro’s soul and his geography, and this is nature. The author uses the same sentiments to bring his characters to life as he does to bring nature to life. Its evocative presence takes on a multitude of forms – voices, sound, light, shade – its world comes alive, unleashing a transformation where it becomes, to all intents and purposes, an extension of the characters’ state of mind.

There is a cast of voices and sounds acting on that blurred area that lies between the soul and the senses: they come from the mountains in moments of solitude or meditation, the sounds of the lake accompany grave or mysterious thoughts, the river rumbles its presence, the rain cries, and the wind moans in anxiety or symbolises the purity of the landscape; but also a well-tended garden, the flowers, chastely pure or sensuously intoxicating and certain types of trees add a climate of intimacy and mirror the characters’ inner world.

For those interested in reading Fogazzaro’s novels and discovering the connections between his works and the places they are set in the Vicenza area, there follow selected excerpts from Daniele Cortis, Piccolo mondo moderno (The Man of the World) and Leila, which show how the characters’ moods are mirrored in the landscape.